the other end of the spectrum

Lessons in adaptation: vaccine delivery in well-resourced countries

Well-resourced systems can still fail. They can also be used to change course quickly and decisively. They are resilient.

The health systems of many higher-income countries had strong existing vaccination programmes, including adult vaccination platforms, plus the financial resources which allowed them to use existing infrastructure to roll out COVID-19 vaccines quickly. However, the volume of COVID-19 vaccinations to be rolled out still created considerable pressure, even for the most established immunization programmes.

How would higher-income countries adapt existing systems to this unforeseen challenge?

These are some of their stories

Singapore

Data accurate as of September 2023

Source: WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard,WHO-UNICEF COVID-19 Vaccination Information HubSingapore initially adopted a zero-COVID-19 approach, trying to stamp out the disease within its borders.

The city-state was able to reopen safely on the wings of a high vaccination rate across its population. This achievement is partly due to the country’s small size and to its free universal health system. But other factors helped.

Combining vaccination with reopening

Rather than implementing a vaccine mandate, Singapore offered more freedoms to vaccinated people as the economy began to open up. For example, vaccinated people had less strict social gathering rules and could meet at restaurants in larger groups.

Clear communication

Singapore combated vaccine misinformation with clear communication campaigns, especially targeted at older people. For example, outreach volunteers visited unvaccinated older people at home to answer their questions, and a music video featured comedian Gurmit Singh playing beloved character Phua Chu Kang, who urged people to get vaccinated.

Singapore

People walking in a Singapore street during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Explore other case studies

Denmark

Data accurate as of September 2023

Source: WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard,WHO-UNICEF COVID-19 Vaccination Information HubDenmark’s mass COVID-19 vaccination programme was successful in achieving what the Government described in April 2021 as ‘sky-high’ vaccination levels.

Based on this success, Denmark shifted to focusing on at-risk populations – such as older people and the immunocompromised – ahead of winter. What’s behind Denmark’s success?

A robust plan

Health authorities mapped out a staged plan, driven by specific goals, to distribute the vaccine and reach target populations.

Accessibility

The Danish health system is universal, and vaccination is free. It’s available to citizens and to people resident in Denmark for longer than 30 days. Vaccination at hospitals was focused on health and care workers, while pop-up vaccination centres and mobile units ensured good coverage across the country in other population groups.

Digital data

Citizens have a profile in the Danish Vaccination Register, which is tied to their national identification number. This is a critically important part of strong data systems: strong civil registration and vital statistics systems. Individuals received invitations via secure email to digitally book a vaccination. Once a person received a COVID-19 vaccine dose, their vaccination record was updated.

Trust and transparency

People in Denmark have high trust in their government and its ability to manage the pandemic. No vaccine mandates were implemented. Health authorities continued to collect data on attitudes towards vaccination as the programme progressed, allowing them to tailor and target communication efforts.

Explore other case studies

Portugal

Data accurate as of September 2023

Source: WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard,WHO-UNICEF COVID-19 Vaccination Information HubAn initial surge of COVID-19 cases nearly brought Portugal’s health system to its knees. The country rebounded with a huge vaccination effort.

Portugal built on its historic experience with polio vaccinations in the 1960s. Nearly all eligible adults have now been vaccinated, and it was one of the fastest countries to reach 70% coverage in the European region.

Choosing influencers carefully

A naval officer, Vice Admiral Henrique Gouveia e Melo, took charge of Portugal’s vaccine rollout in February 2021. This was the most difficult phase of the pandemic for Portugal, with public hospitals near collapse and expected vaccine deliveries yet to arrive. Public trust in the rollout was waning. Gouveia e Melo stepped in to front public communication efforts on television with strong messaging and a no-nonsense approach. His straight-talking style alleviated public fears around the rollout and reassured them that they would get vaccinated in time. Gouveia e Melo says the key to his success was presenting vaccination as a social issue rather than a political one.

Additionally, 5000 micro-influencers were enlisted by the Portuguese Directorate-General of Health to build confidence.

The influential community members became “listening posts” for community concerns about COVID-19 measures and vaccination. They spread reliable information and fed back any doubts or confusion to central health authorities. These micro-influencers were embedded across society, meaning even hard-to-reach communities had a trusted person with whom to discuss their questions or concerns. Together, they showed how powerful a chorus of trusted voices can be to encourage vaccination.

Explore other case studies

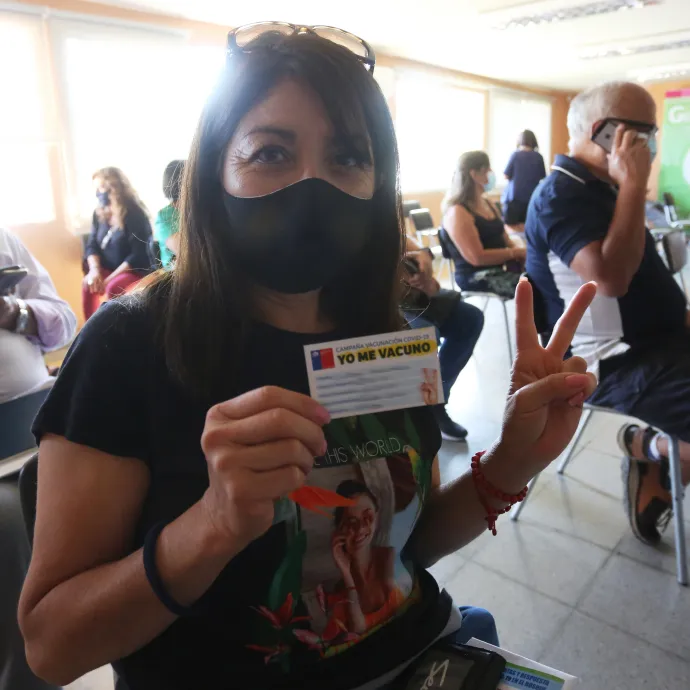

Chile

Data accurate as of September 2023

Source: WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard,WHO-UNICEF COVID-19 Vaccination Information HubAfter grappling with a severe outbreak early in the pandemic, Chile emerged as one of the first countries to begin their vaccination campaign.

Vaccination for health and care workers began in December 2020, with a nationwide rollout subsequently kicking off in February 2021. Chile vaccinated more than half a million people within the first 3 days of making the vaccine available to the public. How did Chile turn vaccines into vaccinations?

A diverse vaccine portfolio

Chile obtained a range of vaccines early and from different sources. It also hosted vaccine clinical trials for several candidates, giving it an edge when brokering deals with pharmaceutical companies.

Strong primary care system

While Chile has a mixed public and private health system, it has a comprehensive network of public primary care clinics that cover the length and breadth of the country. These public primary care clinics are well connected to the communities they serve, facilitating local delivery of the vaccination programme, and even the smallest are equipped with cold chain capability for vaccine storage. Due to Chile’s experience in vaccinating adults against influenza, they also have vaccine delivery platforms targeting adults as part of their primary care system.

A history of mass vaccination campaigns

Chile’s national immunization programme dates back to the country’s efforts against smallpox in the late 19th century. It has run seasonal flu campaigns since the 1980s. After the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, Chile invested in its vaccine infrastructure, including installing the special freezer storage and supply chain needed for some advanced vaccines. This logistical capability proved valuable during the COVID-19 pandemic. An electronic vaccine registry established in 2011 enabled accurate, near-real-time data tracking through the country and tracking of vaccination coverage by population groups, including health and care workers. Chile’s long tradition of vaccination helped shape a culture characterized by public trust in vaccines.

Meeting people where they are

Chile set up hundreds of mobile vaccination centres in schools, football stadiums and markets, including drive-through centres in parking lots.

Clear and easy vaccination schedule

No appointment was necessary to receive the vaccine. It was offered for free. A clear and simple vaccination schedule, standardized nationwide, made it easy for Chileans to know when they could get vaccinated. Each day of the week was assigned to a certain group – for example, a Wednesday might be for people aged 54 and 55 years with underlying conditions, while Thursday might be for those aged 50 to 53 years.