Delivery

Turning vaccines into vaccinations

Attempting to deliver COVID-19 vaccines to the world’s entire population of almost 8 billion people required overcoming unprecedented challenges, well beyond the requirements of a routine vaccine rollout.

By the end of April 2021, nearly every country had introduced the vaccine. And by the end of 2021, COVID-19 vaccine supply was sufficiently scaled to move large numbers of doses into countries around the world. The pressing question then became: How could the vaccines get to where they were needed in order to vaccinate those most at risk?

Until they're all vaccinated, I'm not giving myself peace.

COVID-19 vaccine delivery: a unique set of challenges

Starting from a zero-immune population

Because the virus that causes COVID-19 was entirely new, health authorities were working with a population without any pre-existing immunity: the entire global community was at risk.

Reaching broader population groups

The vast majority of global immunization efforts target children, who are born with little to no immunity to major diseases. But in the case of COVID-19, adults were completely lacking immunity, just like children. Adults, especially older adults, were also at much greater risk of serious disease from COVID-19, which was a new challenge when compared to many other vaccine-preventable diseases. Governments around the world had to take new approaches for COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, in order to reach much larger and more diverse groups of people. This was particularly challenging in countries that had not previously introduced adult-targeted vaccines such as the influenza vaccine.

.jpg_1920.webp)

Residents of the village of Makontakay, Sierra Leone, meet under a mango tree to be vaccinated against COVID-19 by a mobile health team.

Targeting specific sub-groups

Even within the adult population, COVID-19 vaccinations needed to be targeted to populations at increased risk. Health and care workers, who come into contact with other people in the course of their essential work, needed to have confidence that they could be kept safe from potential serious disease. The immunocompromised and older people were at higher risk of serious illness and death. This presented new challenges for many countries, especially those without comprehensive public health systems, up-to-date census data or efficient ways of identifying how many people were in these specific target groups or where to find them.

Proportion of target groups with a complete primary series BY COUNTRY INCOME GROUP

September 2023

When I saw the delivery of the COVAX, I said ‘wow. It has really landed. We are going to take it. We are going to reduce COVID-19, which is going to reduce our stress.’ And lo and behold, they started with health workers. Frontline workers were prioritized because we were with the patients. I made sure that first day I would be the first person to have my vaccine.

Rolling out and scaling rapidly

The ability to rapidly deploy the vaccine across entire populations was dependent on the resources available to each country. Financial resources, and also the strength and structure of their existing health system, determined how quickly countries could scale up to reach sufficient vaccination rates.

Peak COVID-19 daily vaccination rates by country

The majority of high- and upper-middle income countries reached their peak daily vaccination rates earlier in the pandemic than low-income countries.

Angola

WHO staff speak to a health worker involved in COVID-19 vaccinations at a vaccination centre

Accessing information for planning

Planning is a crucial component of vaccine rollout and distribution. But in the case of the COVID-19 vaccine, the information needed for planning was sometimes limited – and what information was available was changing rapidly from day to day. Planners had to be able to think fast and adjust plans to work with the distribution methods available – it was a constant exercise in problem-solving and innovation.

Handling new vaccine products with unique storage requirements

There was no one-size-fits-all solution for COVID-19 vaccine delivery. The newly developed vaccines had unique characteristics, so new technologies and processes were needed for their distribution and administration. For example, different vaccines had to be transported and stored at different temperatures. Some needed to be kept between 2°C and 8°C; others between -25°C and -15°C; and some even colder, between -90°C and -60°C. Not all countries could meet the new and complex requirements of the ultra-cold chain, which meant considerable upgrading and training. This challenge was intensified in countries with high local temperatures.

Nepal

Gorkha District

Women queue to receive their COVID-19 vaccine at Chiwinga Village in Kasungu District, Central Malawi.

Managing competing humanitarian crises

COVID-19 was a crisis everywhere. Yet in many countries, it was just one of many compounding humanitarian crises. Wars. Civil unrest. Droughts and food shortages. Economic failings. Political instability, and increasing numbers of refugees and internally displaced people. Before COVID-19 even arrived in their countries, many people were already fighting for their lives. As COVID-19 ran rampant through crisis-affected countries, vaccine supplies had to be moved across unsafe territories, demanding efforts above and beyond the norm as health and care workers, community mobilizers and volunteers worked to set up temporary clinics.

Paying for it

Vaccines don’t just appear out of thin air, ready to be administered into people’s arms. Getting vaccines into arms requires entirely new channels of fundraising, investment, budget allocation, approval and distribution, and health and care workers to administer the vaccine. Vaccine delivery budgets also had to stretch to meet a range of needs across already underfunded health systems: to provide safe and efficient vaccination, facilities had to be repurposed and workers had to be paid. Many health and care workers in low-income countries even went unpaid for their labour. These workers’ efforts transcended their duty of care – they were fighting to keep their communities alive.

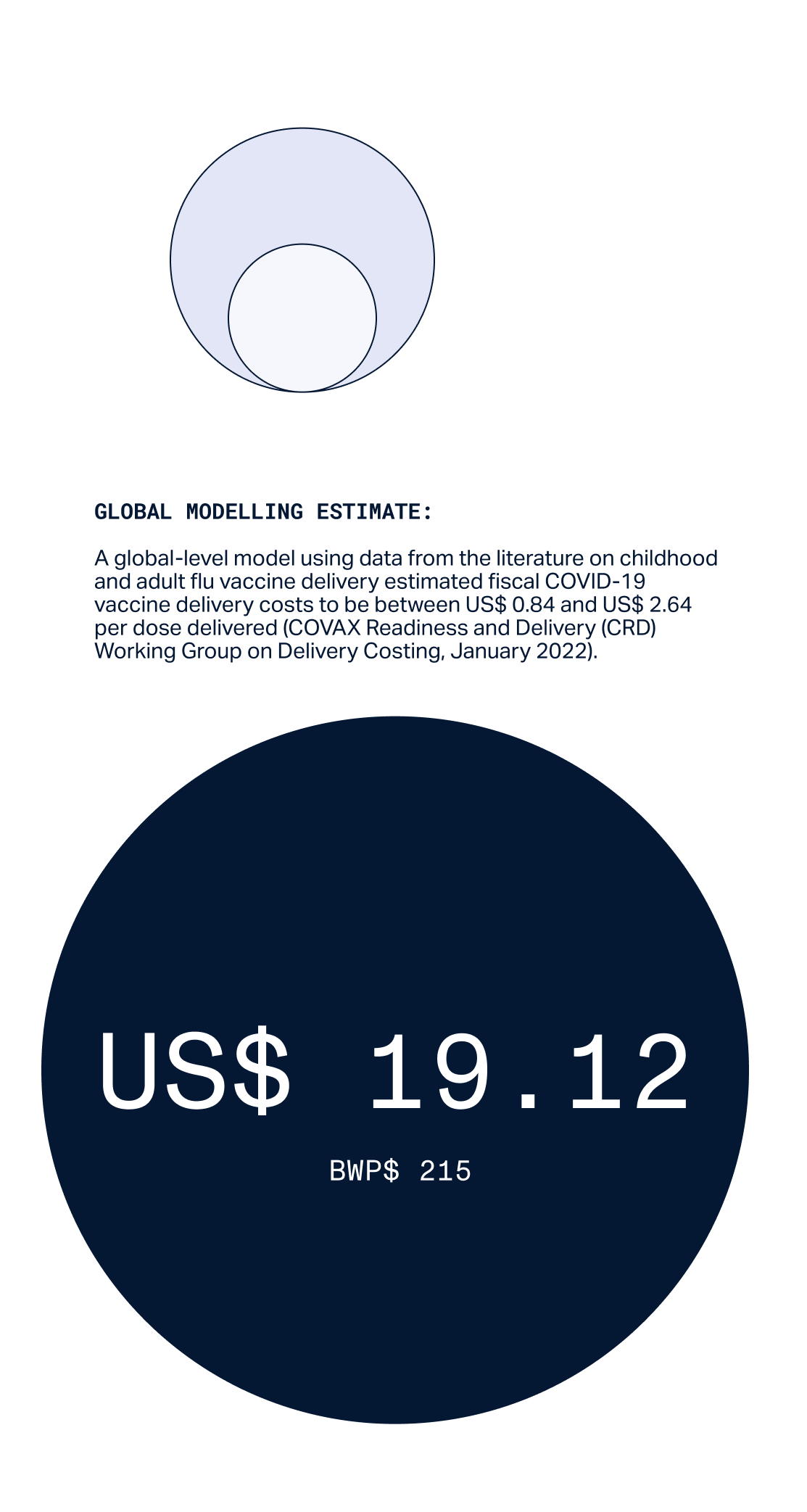

covid-19 Vaccine delivery costs case study

Estimated COVID-19 vaccine delivery cost vs Botswana actual cost

Sierra leone

Community mobilizer and chiefdom supervisor Mohamed visits Mamanso, Sierra Leone, to educate residents about COVID-19 vaccination.

Battling misinformation and vaccine hesitancy

noun. a motivational state of being conflicted about, or opposed to, getting vaccinated; this includes intentions and willingness. (Source)

Not all countries had clear, reliable government communications around the science and safety of COVID-19 vaccines. In fact, in many cultures and countries, both high- and low-income, the battle against misinformation proved to be a huge barrier to delivery. From mistrust of large pharmaceuticals, government services and policies, to a reliance on natural or traditional medicines, there were a range of beliefs that influenced people’s attitudes to vaccination. For many people, their mistrust stemmed from the fact that this vaccine was new and had been developed so fast – not understanding that it was built from years and years of research on other viruses in the same family. Helping the public understand the benefit of getting vaccinated was a significant task.

The rumor was if a pregnant woman gets the vaccine, she would lose the baby. My baby, Harriet, is now 7 months old. I got vaccinated to protect her so she can become an important person in future.

Nancy Kenyi Nyoka, Mother of 3 children, Worinya Tank 21, Palorinya Refugee Settlement.

Going above and beyond: right arms, right places, right times

Standard mass immunization campaigns worked for COVID-19 – but only up to a point. The key priority that quickly emerged was the critical need to focus on the world’s most vulnerable: older people, the immunocompromised and those on the healthcare front lines.

With this in mind, micro-campaigns were tailored to meet the needs of specific individuals, cultures and communities.

“This is what I said and what we have used to win them over: If a stranger suddenly enters your house, you react by fighting him. But when you realize he came to train you how to fight a big real enemy who has already entered your village, you become friends and learn the fighting tactics, that is multiplying antibodies, so when the enemy reaches your house, you stop him successfully. We registered all eligible people and the response is good; we shall hit the target.

One collective step towards progress

The challenges of this delivery led to some of the greatest learnings of our lifetime around mass health campaigns and how to get adult populations vaccinated.

They sounded an urgent warning about weak health systems, while at the same time offering an opportunity to help strengthen them: to invest in vulnerable and underresourced countries and move towards greater pandemic preparedness worldwide.

The stories of this delivery underline the need for a tailored approach in order to reach the communities who need protection the most. They also reveal an incredible human triumph: our global community joined forces, coordinating in partnerships and overcoming seemingly insurmountable challenges to protect one another.

The COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery Partnership

Recognizing the urgency of turning vaccine doses into vaccinated, protected communities, Gavi, UNICEF and WHO launched the COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery Partnership (CoVDP) in January 2022.

The Delivery Partnership (which transitioned back to partner agencies in June 2023) was built on existing resources to support the AMC 92 and focused on the 34 countries at or below 10% vaccination coverage in January 2022. Working closely with countries to understand bottlenecks to vaccination, the Delivery Partnership offered access to urgent operational funding, technical assistance and political engagement to rapidly scale up vaccination and monitor progress towards targets. The Delivery Partnership was the next phase of the Country Readiness and Delivery (CRD) workstream. It built on the substantial body of work realized by CRD, that was part of COVAX since early 2020, and which made available global guidance and coordinated technical support for the implementation of COVID-19 vaccines. This partnership became a key factor of success within many of the following COVID-19 vaccine delivery stories.